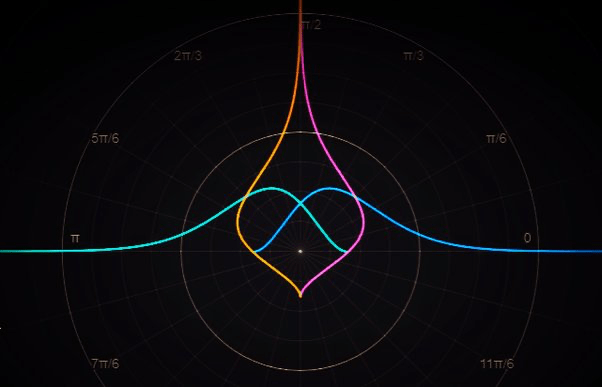

We often describe compassion as love or empathy for others—but what if we understood it as a mathematical relationship? In particular, through the lens of linear algebra: as the interaction between two vectors in space.

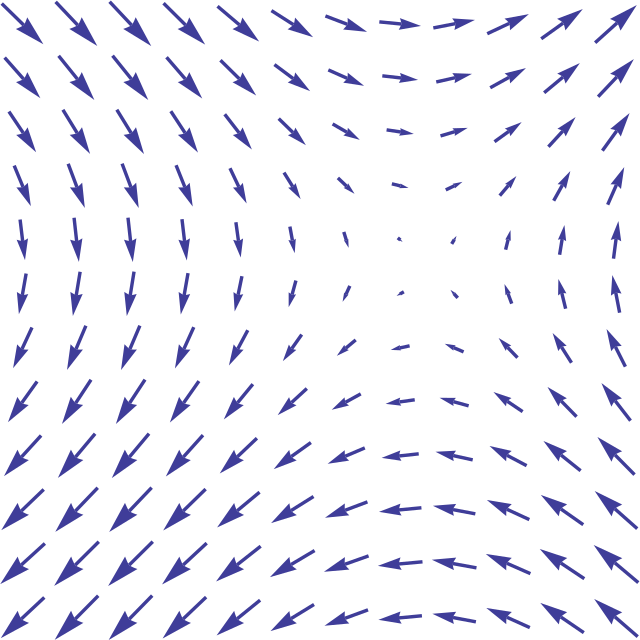

Imagine two vectors: one representing yourself, and one representing the universe. At first glance, they may seem completely unrelated—orthogonal, even. In linear algebra, orthogonality implies two vectors are perpendicular; they share no direction, no similarity. But despite their independence, each can still be projected onto the other.

Photo by Frank Tunder on Unsplash

The projection of the universe onto ourselves is what we perceive: our lived experience, our interpretation of the world. This projection carries a sign—positive or negative. When this projection is positive, it becomes the foundation of compassion: our capacity to understand, resonate with, and care for what we see around us. Compassion, then, is not the illusion that we are the same as everything else, but the ability to meaningfully relate—even when difference remains.

When the projection is negative, what are we left with? Perhaps resentment, alienation, fear. We still feel the universe—we cannot escape its projection—but we recoil instead of embrace. The direction of the projection shapes the quality of our relationship with the world.

On the other side, the projection of ourselves onto the universe is our impact: what we give, how we influence the field around us. Our impact may also be positive or negative, depending on intention, awareness, and alignment.

In this framing, compassion is not passive. It’s a directional vector. It arises when our perception of the universe aligns positively with our internal orientation—and when we choose to act from that projection.

To be compassionate is not to dissolve into sameness. It is to honor difference while still projecting warmth, resonance, and care. It is mathematical, even beautiful: the quiet geometry of love through understanding.

A Note on Limitations

Of course, this is a simplified metaphor—a perfect world drawn in clean geometry. In reality, our projections are not direct. Between ourselves and the universe lie countless obstructions: other people, systems, memories, and misunderstandings. The line is rarely straight.

But this does not mean we should stop trying. Even if our compassion cannot reach the universe in a single vector, it may ripple through the field, touching others, bending around obstacles, amplifying in surprising ways. Our intent still matters. Our direction still matters. And our effort to understand—to project love across difference—remains one of the most radical acts we can make.

How to deal with this complexity? I’m still exploring. Comment below if you have thoughts on it.

Leave a comment